In these “uncertain times”, doing much of anything can seem like an impossible task when burdened with the daunting reality of surviving a global pandemic. Not only are people and their loved ones faced with immediate health threats just by leaving their homes, but many are threatened by a recession marked by high unemployment rates and a further divide in economic inequality, as well as a constant news cycle spouting apocalyptic narratives in regards to the pandemic, climate change, the political landscape, etc. All of these forces combined have undoubtedly taken a toll on many, especially mentally. Since the beginning of quarantine in March until now, six months later, I’ve oftentimes thought of it as almost pointless to partake in things I’ve always held as crucial to my identity and sanity, such as creating, while being inundated with this barrage of crushing messages about the present and future. Myself and possibly many artists, creators, appreciators, etc. have gone through a similar thought process, asking whether or not art is essential when our livelihoods and material reality are at stake.

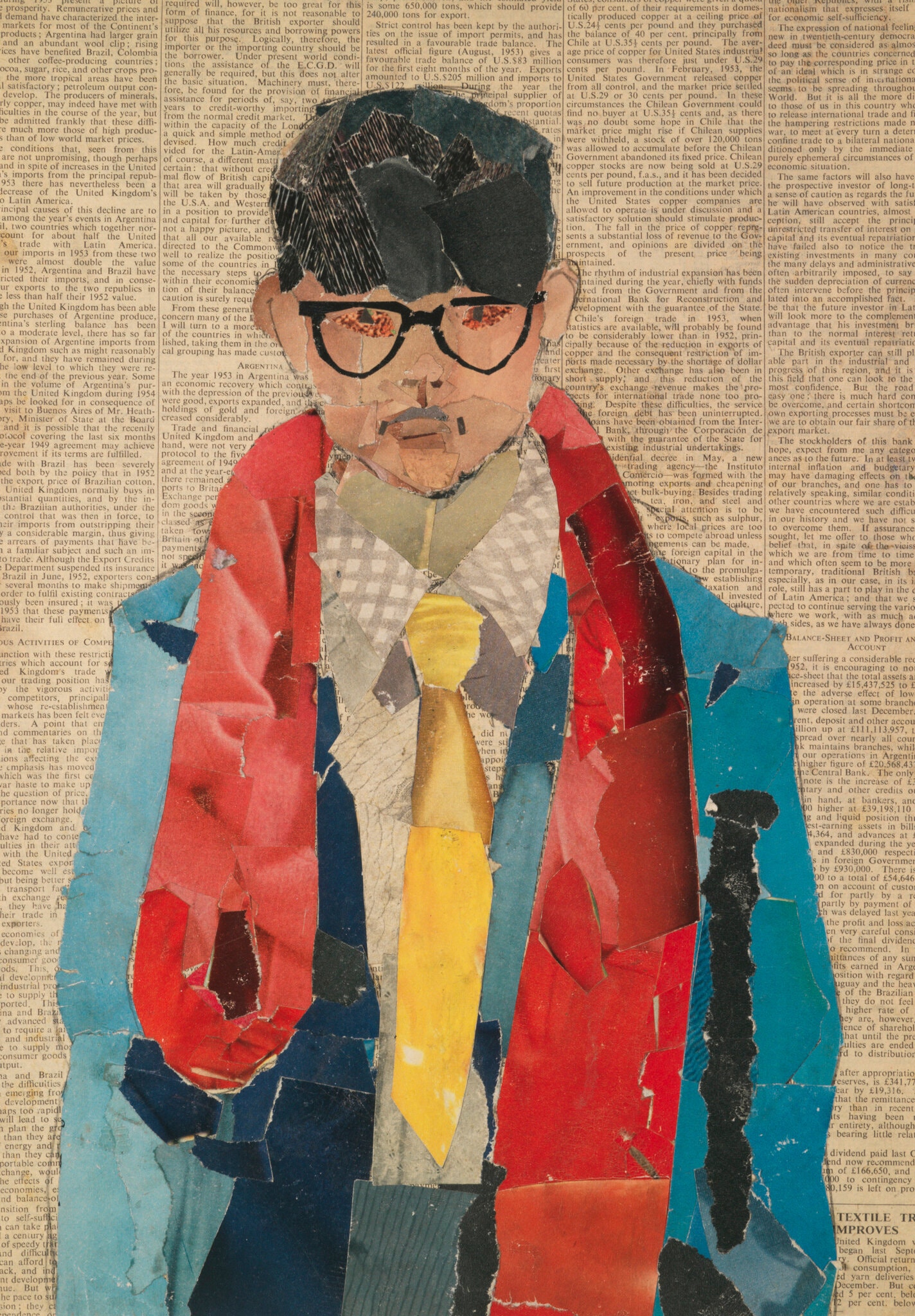

Grappling with this same question, M.H. Miller in “In a Time of Crisis, Is Art Essential?” examines the nature of artmaking and how artists are overcoming adversity through creating. In one beautiful summarization, Miller writes “All art is an act of faith — a faith that life itself, with all its tragedies and flaws, can be improved by creating something new and putting it out into the world.” Of course, the author’s response to the question of whether or not art is essential is a resounding yes. I think what Miller is saying is that art is not a luxury or an indulgence tied to prosperous moments in history, but instead an innate need in humans regardless of the material circumstances around them to transcribe their emotions or ideas and to leave something behind when they’re gone. Humans have continued to persist through strife and struggle and have managed to create, whether it be artists on the front lines of WW1 portraying the destruction and reduction of humanity in war, or persecuted queer artists working in underground subcultures.

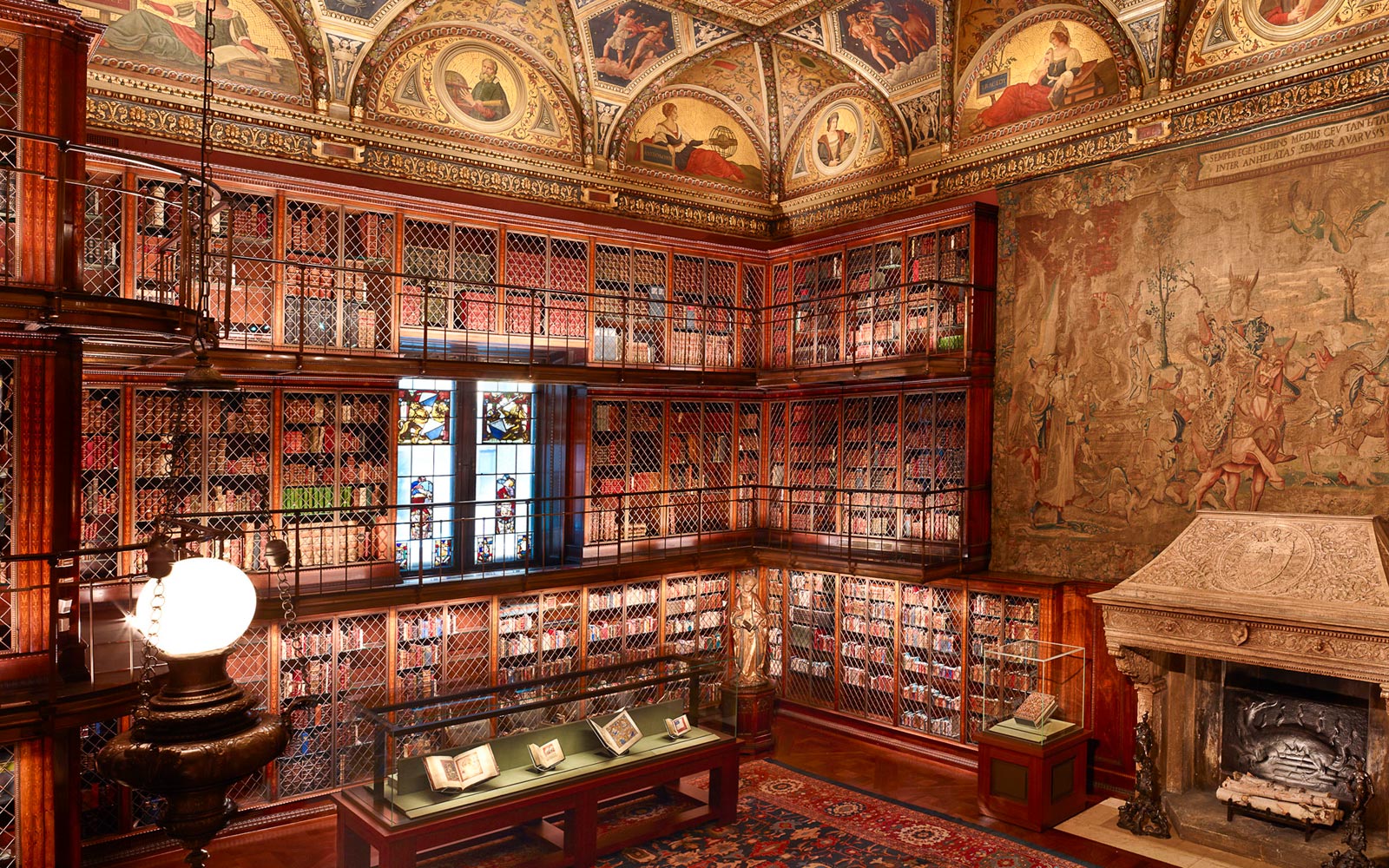

With this said, art offers the alternative and subjective experiences of real people that you cannot find in a history book. Art too serves many more functions besides acting as historical snapshots, and these functions and the need for them transcend negative circumstances such as the current pandemic or times of war, famine, etc. in the past. Art will forever hold a place in human culture, whether it be for more practical needs such as ceramics or decorative tools, to more metaphysical human needs such as connecting with the spiritual through art or coming to grips with one’s lived experiences by using art as a form of therapy. Not only this, but art is inherently a communicative tool used to bridge contact between the artist and the viewer, and in a time where offline human contact has been drastically diminished, art is especially important now in reducing our isolation and connecting one another. This article has helped reinstate my love for art and realize its importance as a human need, not a luxury, and come to the realization that art might just be needed now more than ever.