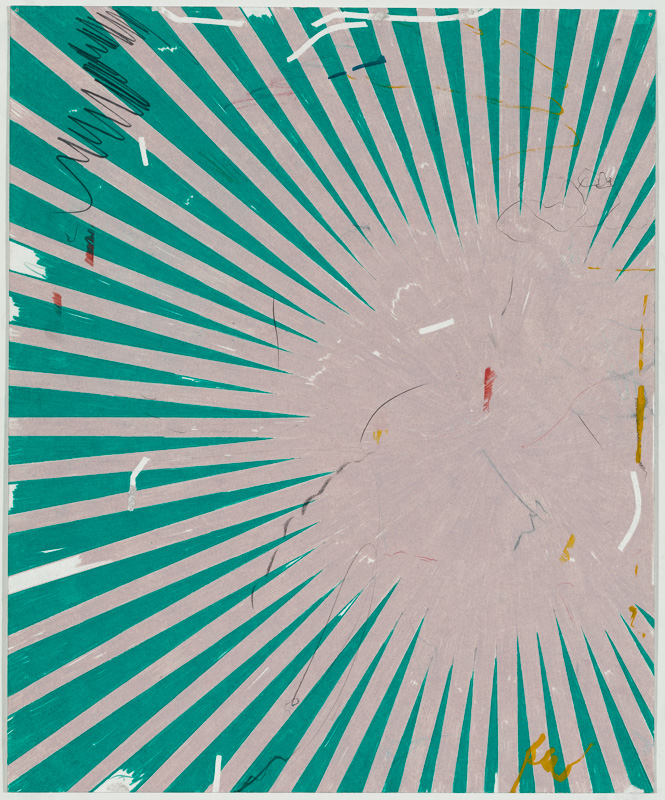

This week, artist Amna Asghar gave a fascinating artist’s talk about her work, processes, and philosophies. Asghar, a Pakistani-American born artist based in Detroit, creates paintings and screen prints that often reappropriate imagery, especially images from or involving Pakistan and the Middle East. Some source materials include skin whitening ads from magazines, Orientalist paintings, restaurant menus, as well as Disney movies, but she puts together slices of these images to put them into a new context and perhaps in an attempt to reclaim her identity.

Amna Asghar, Portal II (Egypt), 2019

screenprint and acrylic on canvas

20 x 14 inches, 50.80 x 35.56 cm

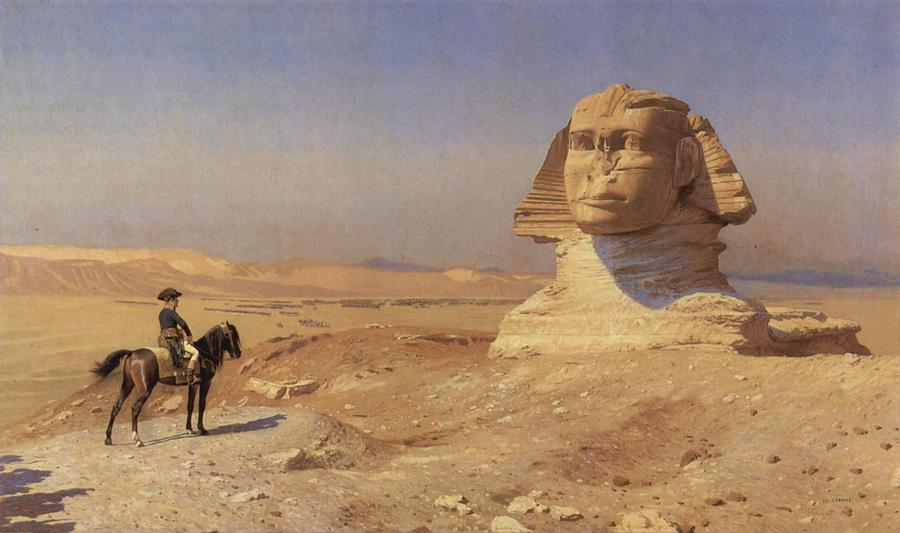

For one, I really appreciated Asghar’s approach to art making, specifically in terms of reappropriating images for one’s own purposes. Her work often borrows from images of non-western cultures produced by westerners, such as the Orientalist paintings by Jean-Léon Gérôme and Disney movies such as Aladdin. Our conceptions of culture and places are undoubtedly formed, at least partially, by the media we consume, and I admire that Asghar is examining and challenging these bits of media and our conceptions of cultures that can often be rooted in colonialist attitudes. In doing so, she is also reclaiming her identity and culture as Disney and the Orientalist painters “don’t have ownership of depicting brown people a certain way”. And while she is dealing with heavy themes such as these and the trauma endured by POC, she says that she often portrays them in a light and humorous manner as “it’s the only way to do it”. While some situations or topics may need a certain amount of gravity or seriousness, I definitely agree that making light of difficult topics or trauma can help one begin a conversation and make sense of the world, as well as instilling a sense of comradery in a community. I also found it fascinating that Asghar seemed almost annoyed when asked about identity, as she is probably constantly asked questions about her identity as a POC artist. It’s almost as if she is pigeonholed into doing “identity” work, when in reality she says that all artists are creating works about identity, as you can’t quite separate the art from the artist.

Another element of Asghar’s art that I really admire and have been thinking about with my own work is the disconnect between our conception of space and real locations. I obviously cannot speak for her about her own emotions and experiences, but a lot of her work such as the pieces taking imagery from Aladdin and Gérôme are of the Middle East, and could possibly be incorporating ideas about her having grown up in America and having seen these locations and Pakistan through the lens of media and art rather than physically being there. In the case of Asghar’s art, she might be critiquing this media for colonialist attitudes and romanticising cultures in a one-dimensional way. While I don’t have quite the same relationship, I (and I’m sure most people to an extent) tend to romanticize places I’ve never been to, and if I ever have the chance to actually visit these locations, they never meet my expectations that I have formed through media.

acrylic on canvas

36 × 25 inches, 91.44 × 63.50 cm