This week, we had a fascinating conversation with art critic Eleanor Heartney centered around the very timely theme of “doomday” in art. Heartney had recently published “Doomsday Dreams: The Apocalyptic Imagination in Contemporary Art”, a book exploring apocalyptic narratives in art spanning centuries, from ancient Zoroastrian art to contemporary times. Heartney argues that the concept of “the end of the world” has been “deeply embedded in almost every aspect of Western culture”, especially as the three prominent religions of the western world, being Islam, Judiasm, and Christianity, all feature their own versions of the apocalypse in which the world is destroyed and every person faces judgement. And while the contemporary art world is seemingly more removed from religion, Heartney finds that ideas about the apocalypse still inform artists today, especially as the political and ecological state of the world seems more dire.

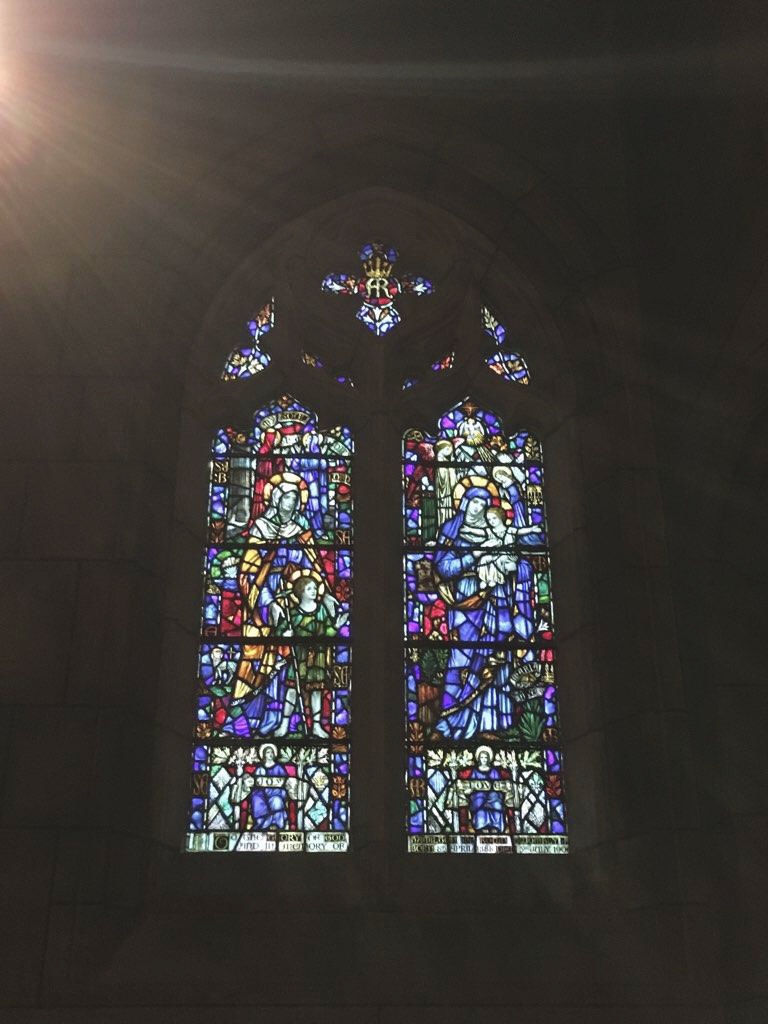

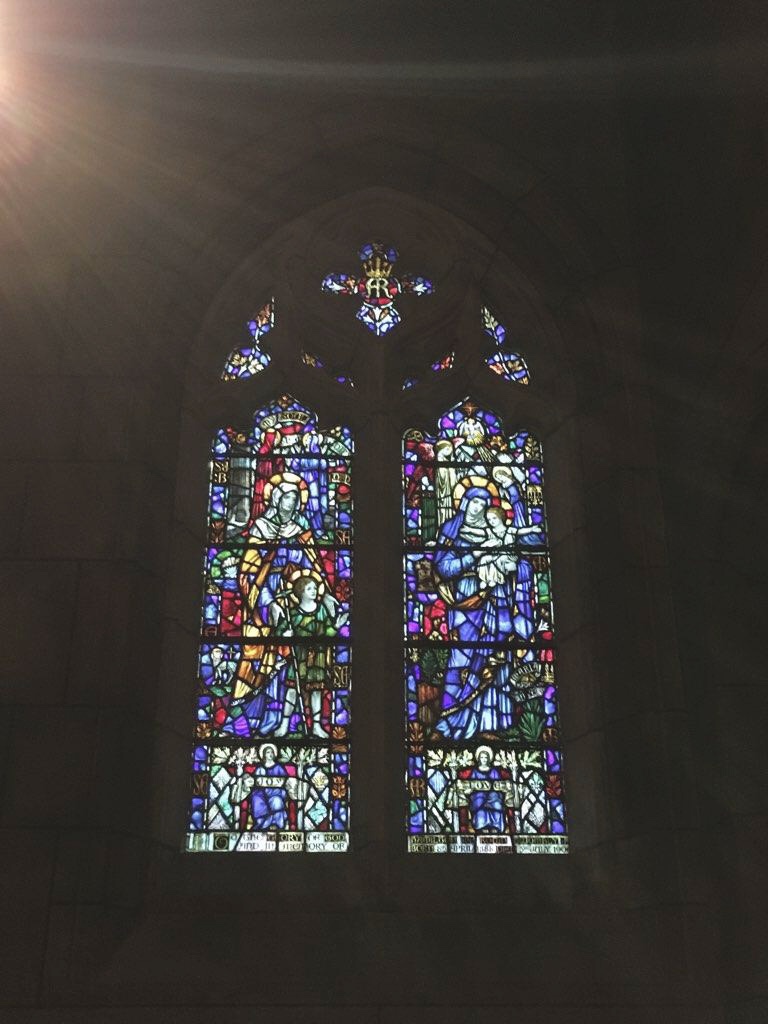

For one, I heavily related to Heartney’s upbringing as well as her views on art and religion. Describing herself as a “lapsed Catholic”, I also grew up in the Catholic church but gradually stopped attending and don’t really identify as being a member of the church anymore. While I understand and recognize the harm organized religion can bring and the ways in which it can be molded to fit political agendas, both being contributing factors to why I don’t attend church anymore, Heartney recognizes the profound influence religion has on art and our worldviews. While religion was of course the main subject manner of art for centuries, especially throughout the Classical, Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque eras, I think its influence is unappreciated in contemporary art despite religion not being so entwined with art as it was in the past. Heartney described so many Post-War and contemporary artists as having grown up religious, and while their works may not be explicitly about religion and they may not identify as religious anymore, their upbringings molded who they were and subsequently the art they make.

As I said, I don’t identify as Catholic anymore, but the values and aesthetics of the church are forever ingrained into my personhood for better or for worse (such as the “fire and brimstone” ideas of the apocalypse), and the rich artistic tradition of the church still informs my tastes today which I think holds true for most people of whatever religion or culture they grew up in. And while I think religion has a lot of negative baggage as of late, and sometimes rightly so, I think that anthropological ideas about religion in which it can instill a sense of meaning in one’s life and communitas should not be ignored.

I also appreciated Heartney’s optimism when faced with such a dark topic in what seems like such a dark time in human history. It’s easy to become defeatist and nihilistic when faced with such a polarized political climate and a ticking climate crisis, but Heartney suggests that by creating visions of utopic ideals in art we can start transferring these concepts into the real world instead of wallowing in these images and feelings of despair.