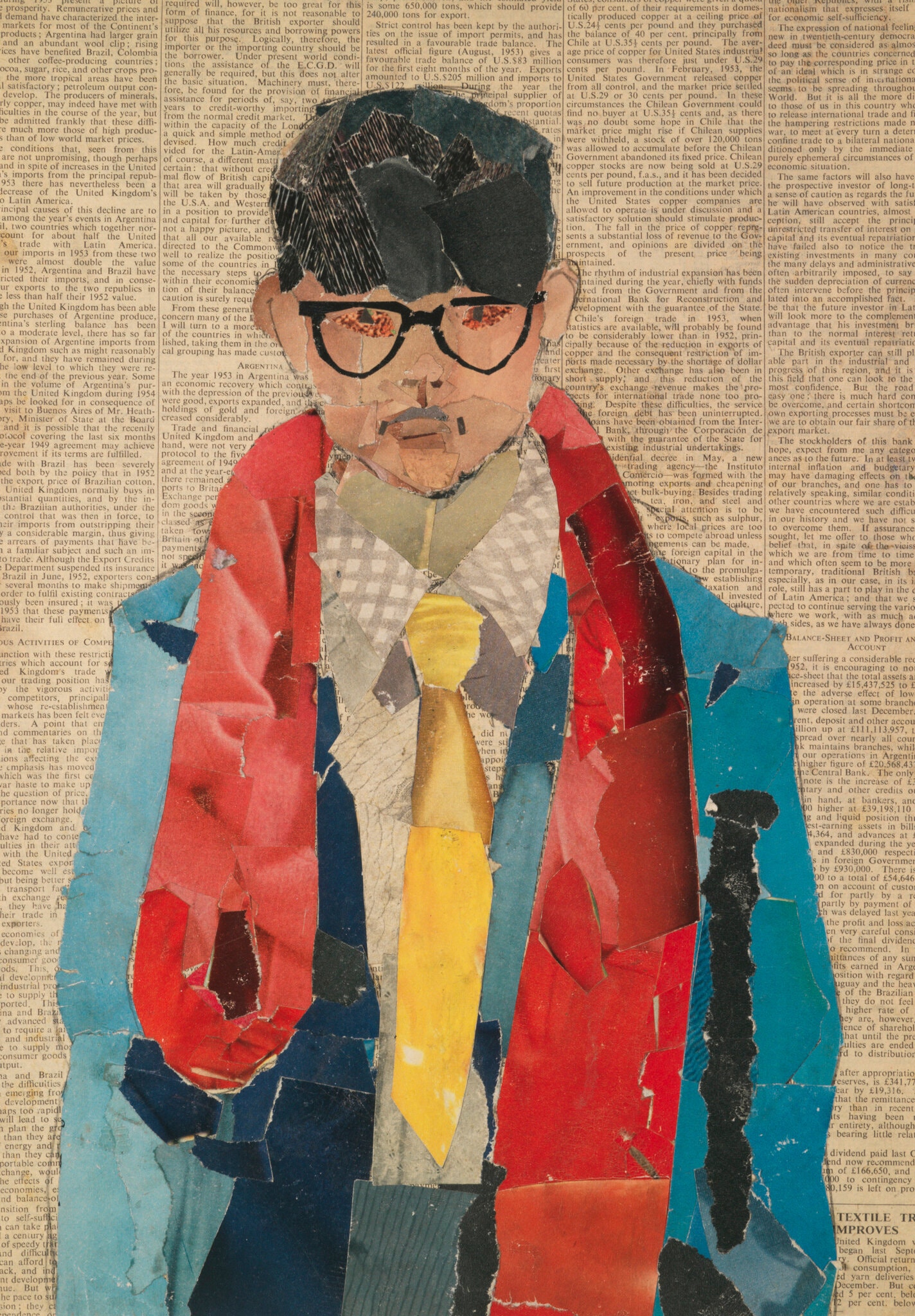

Currently exhibiting at the Morgan Library and Museum in Manhattan, “David Hockney: Drawing From Life” showcases 125 of the renowned artist’s portrait drawings of loved ones, ranging from a variety of mediums such as pencil, charcoal, ink, printmaking, composite polaroids, and digital iPad drawings. These drawings span Hockney’s life and career, one self-portrait collage in particular being made in 1954 when the artist was only 17 years old and studying at the Bradford School of Art, and another drawing made as recently as 2019. We follow a close selection of friends, family, and lovers throughout this decade-spanning stretch of time as they age, since the exhibition only includes five figures: the artist himself, his mother, his one-time lover and longtime friend Gregory Adams, the textile designer Celia Birtwell, and collaborator Maurice Payne. In reviewing the show for the New York Times, Roberta Smith writes “each has embraced aging a different way — Ms. Birtwell most buoyantly, her open face reflecting the artist’s own unfailing curiosity.”

Roberta Smith begins her review of “David Hockney: Drawing From Life” by tugging at the heartstrings:

Whether we’re related by blood or not, our loved ones have been very much with us these last several months. Some have been physically with us, at our elbows, sheltering at home, strengthening and sometimes straining the ties that bind. Or they are with us in absentia, in yearning, across great distances, sometimes oceans. Others are no longer among the living; their absences may have been caused by the current pandemic, leaving a fresh painful void and the suspicion that they died in vain.

While it may be somewhat trite at the moment to center the show and her review around the pandemic, it’s nonetheless an effective and relevant opening. The last few months have resulted in the average person becoming overly sentimental towards loved ones, and rightfully so, perhaps making “David Hockney: Drawing From Life” the perfect show for a time when it’s important to contemplate on close relationships as Hockney does in this treasure trove of portraits.

Smith goes on to elaborate some of the main themes she found within the show, such as friendship/intimacy of course, “the glory of drawing in various materials and styles”, and time as “Drawing from Life” is divided into five chapters in chronological order, showcasing his loved ones aging in different moods and settings. I think that the decision to focus on a small core of intimate relationships helps make this show even more poignant, as Smith’s description of these five figures makes it sound as though we get to know them on a personal level as they age, and including too many people in the show wouldn’t pack quite the emotional punch. Smith writes about Gregory Evan in particular as “he begins as a tall boyish beauty with cascading curls (depicted with fine, Matissean sparseness), and is almost unrecognizable as an imposing older figure, heavier and scowling through eyeglasses in a large ink drawing at the show’s end.” While Smith doesn’t explicitly say it, it seems like the show inherently deals with our fear of death and of loved ones aging, again helped by Hockney’s choice to portray a select few individuals, many of whom begin as youthful and fresh-faced in the drawings, physically age through the decades.

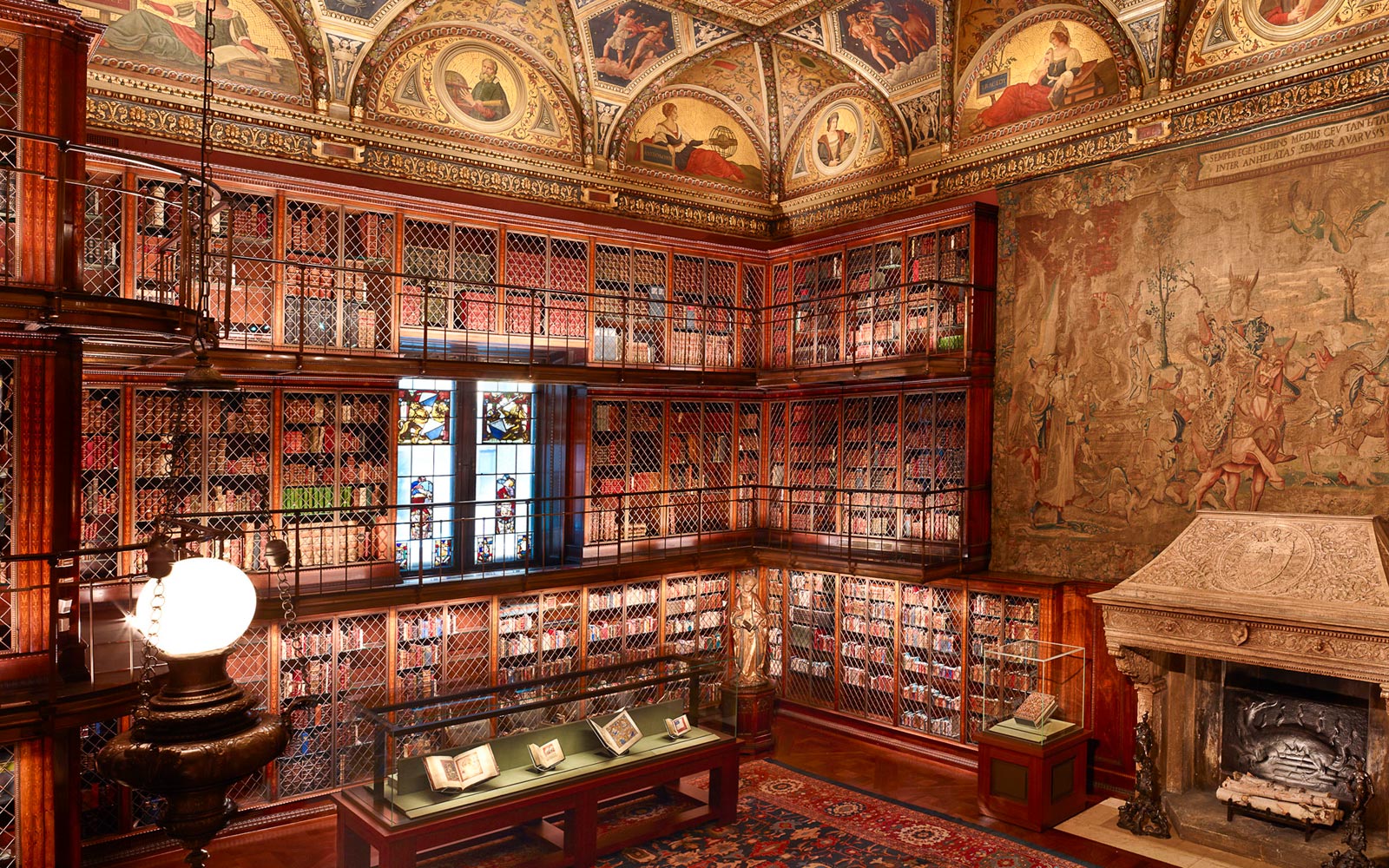

Smith doesn’t necessarily offer a definitive review of “David Hockney: Drawing From Life” and throughout the article mostly examines the themes of the show and a few select pieces rather than offering conclusive judgements, but I would say she overall speaks of the show extremely favorably and doesn’t pose any criticisms. The way she talks about “Drawing From Life” in such human, emotional terms makes me seriously consider journeying to the Morgan Library and Museum even if I wasn’t already a fan of Hockney’s works. I think the most successful art is able to conjure poignant emotions in the viewer and arise a visceral reaction, which it sounds like happened to Smith while viewing the show. In that way, I think Smith’s review of “David Hockney: Drawing From Life” was successful. However, I would have liked her to describe her experience of viewing the show in a more tangible manner rather than just focusing on its emotive qualities, such as describing and critiquing how the show was curated and how its location enhances or detracts from the artworks, going more in depth into the materials and techniques Hockney used, and perhaps talking about what going to a show and viewing art in person is like in a COVID world. Nonetheless, “David Hockney: A Life in Drawing” ends on a strong, touching note with Smith saying: “Approaching paintings in terms of impact, these latest portrayals attest to Mr. Hockney’s undiminished ambition for the medium so central to his achievement. They also attest to the endurance of love in our lives and the role of art in making us see it.”